The Hope Island Race Tragedy of 1982

Introduction

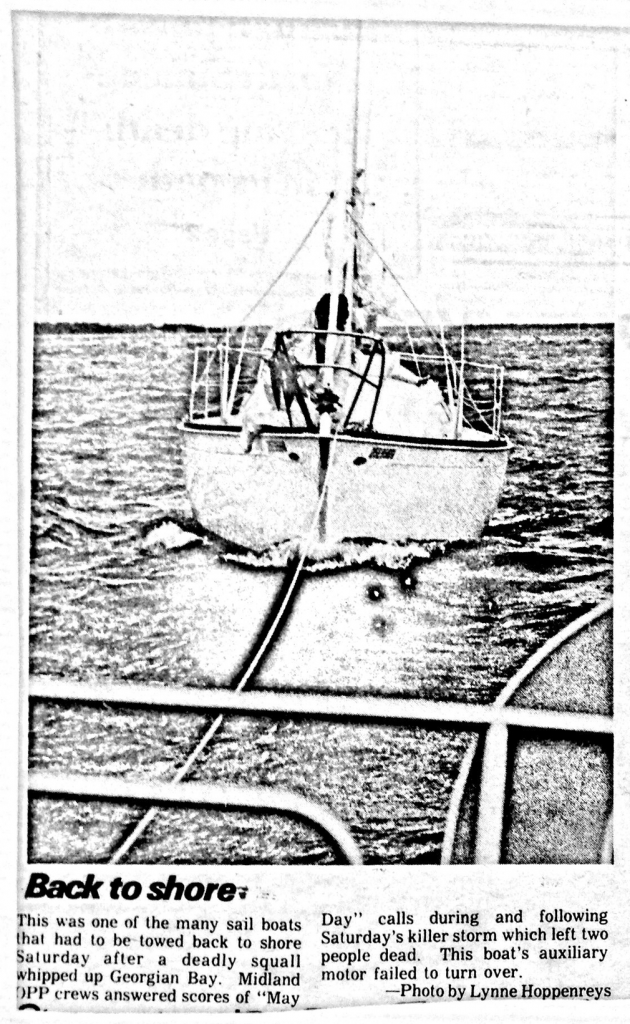

The fierce line squall that swept across Georgian Bay on Saturday, August 28, 1982, produced the darkest day in the history of Midland Bay Sailing Club. The sudden squall caught the fleet in the annual Hope Island Race on what was already a very windy day, and claimed the life of one competitor, Jacques Robitaille of Penetanguishene, who was sailing with Ted Chisholm and Dave Desroches in a Soling. The storm also claimed Norman Wren of Bramalea, Ontario, who was swept off his cruising boat north of the Gin Islands while on the way from Penetanguishene to Bone Island. At about the same time Wren was lost, the storm forced an emergency landing of float plane near Beausoleil Island, en route from Toronto to Pointe au Baril. The plane flipped after landing, and both the pilot and passenger were rescued.

The day after the harrowing race, Bill Byrick set down this vivid account of his experience aboard Emigrant, the Soling of Andy and Lynda Zuidema.

Sailing Story

Sailing had become a passion for both my wife Joanne and I, spending every available moment on the water for the last 4 years. Living on Georgian Bay provided the opportunity to do so.

However, the 1982 sailing season was rather restricted for both Joanne and I, due to my participation in a 40-day historic canoe expedition, Destination Sainte Marie, combined with our family responsibility with Kaitlin age two and Benjamin age six months. As a result, prior to August 28, 1982 we had only been out 8 times. Joanne is a great racing sailor and we competed in the Tecumseth Cup earlier in July and we were fortunate enough to win the race. As per our usual procedure of only participating in the major races, I had decided to enter into the infamous Hope Island distance race, with our boat, Bjarni II, a 20-foot day sailor. Joanne decided to stay with the kids, so I began to recruit crew. I called Dave Parsons, our family doctor and friend, but unfortunately he had to work in emergency at Huronia District Hospital on Saturday, August 28.

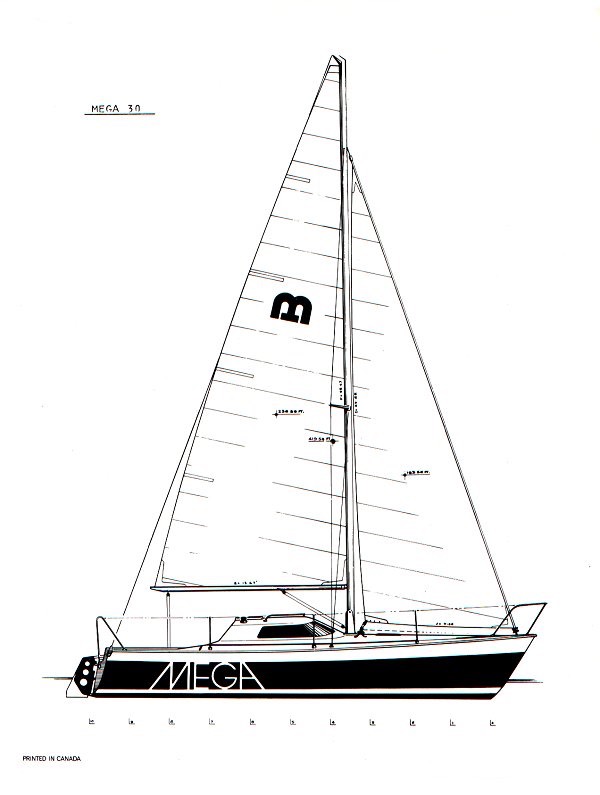

Immediately after I hung up the receiver, Lynda Zuidema called to see if I would be interested in crewing on Lynda and Andy’s boat Emigrant, a 27-foot Soling. [Ed. Note: Lynda is remembered by the Lynda Zuidema Memorial Trophy, donated by the club after her sudden passing in 2006.] A Soling is an A fleet boat and was required to sail the full 48-mile course to Hope Island, rather than the shorter course for the smaller B fleet boats like mine. Andy and Lynda are excellent sailors and I had never sailed in an Olympic class Soling. The thought of both sailing this very fast craft, combined with the opportunity of learning from Linda and Andy, sparked my interest. The chance to sail out to Hope Island was also very appealing and the spirit of adventure caught me so I decided to sail on Emigrant. The decisions took some pressure off as the winds in August on the bay are unpredictable and the thought of being out there in my little day sailor was concerning. I didn’t feel my boat, a 20 foot Cygnus, was seaworthy enough to handle even a small storm. Besides B fleet, designed for smaller craft in which good old Bjarni II would be sailing, was only sailing to Giants Tomb, the 25 mile course. I rarely got the chance to sail out to Hope and this was it. The week prior to the race I heard reports about the efficiency of the Soling in heavy winds. Everyone told me, the boat flies when the wind is “thumping”. I anxiously listened to the forecast hoping for good strong winds. The day before the race the winds were incredibly strong as a front was moving out. I was optimistic.

I was excited about the opportunity of sailing in heavy weather, and not having to worry about the safety of the crew on board. I told my boating friends at work about my upcoming event and they wished me well. Bill LaNauze, a retired naval officer and seasoned sailor, commented on the expertise of Andy Zuidema. [Ed. Note: See the Bill LaNauze Memorial Trophy for more on Bill.] Dave Hudson realized it would be cold and lent me his warm flotation filled coat.

On Friday August 27, Joanne and I enjoyed the Sainte Marie Among the Hurons staff banquet and party at the Midland Golf and Country Club. The party was excellent, but we left early, around twelve, because I knew I would have a long day on Saturday. The last time I sailed in the Hope Island race, I returned at 12 midnight, after 15 hours of tough sailing.

The day had arrived! I woke up around 7:00 a.m., hopped out of bed and hustled to ready myself in order to arrive at the Midland Bay Sailing Club by 7:45. As I was dressing for the day, I remembered the information from the survival course I had taken for Destination Sainte Marie and chose 4 layers of clothing, knowing it would be cold out there. The warmth of wool was one of the many lessons learned from DSM [Destination Sainte Marie], so I donned a good heavy wool sweater and wool socks. Knowing we were probably going to be out there a long time, and remembering the need for carbohydrates to burn in order to produce heat and energy, I had a good heavy breakfast. After preparing myself I raced upstairs to bid farewell to Jo and the kids. I found all three snuggled into our bed enjoying each other’s company. Three quick kisses and I was off for a day of fun and excitement. Little did I know what lay in store.

Upon arriving at the club I found Andy and Lynda at the dock beside their boat. They dry sail their boat because they like to clean the hull and keel after every sail to ensure they minimize any resistance in the water and maximize their speed. Andy and Lynda are two of the club’s most skilled, intense and honest racers. The boats are usually lifted into the water with a small power derrick, but unfortunately there had been a power interruption and the electric winch, which is used to haul boats in and out of the water, was not functioning. Ontario Hydro had been summoned and they were on location rectifying the situation. I took this opportunity to say hello to a few friends who were also participating in the race. Chris Tully was busily preparing his boat at the other end of the lagoon. I commented about my excitement of sailing with Andy and Lynda and of my first experience in a Soling. Chris suggested amiably that I empty my bladder first, as fifteen hours in a Soling is a long time to hold it! The Soling is a 27-foot, open-cockpit, fibreglass shell, similar to a big canoe with all sorts of “go fast” gadgets on board.

Soon the power was on and our Soling was in the water. We moved our boat along the wharf so Dave Desroches could launch his Soling. I recall watching the large keel of his boat Sidewinder, slowly entering the water, and thinking of the fabulous stability of these boats. Lynda introduced me to Emigrant and oriented me to the many lines and devices that controlled the sail and made the boat go. This was truly a racing machine. Andy hustled over to the boat after attending the skippers meeting in the clubhouse and asked if I would like to wear the extra set of foul weather gear. He said it was new but didn’t work real well. He suggested I wear this and leave the coat Dave had lent me behind. I took his advice.

Burke Penny walked over to say hello and gave us the current weather report, wind 20 to 25 knots from the NW, diminishing to 15 knots from the west in the late afternoon. Lynda remarked that I wasn’t going to get the winds I wanted but it should be a god sail just the same.

We left the dock at 8:30 am. There seemed to be the usual tension between Andy and Lynda, as there usually is just before a race with anyone who frequently races together. I was an unknown quantity to Lynda and Andy and I enjoyed the position of limited responsibility and expectation. Andy showed me the hackles which fit around our ankles and told me to put them on. This allowed me to hike out over the side without falling over. In addition, I clipped into the hiking line attached to a harness/vest which allowed me to secure a lifeline from the vest to the base of the cockpit. Alas the real reason they wanted me – moveable ballast!! I recall thinking this is great – I get to sail and get a workout!! At the same time, I thought that this was potentially rather dangerous, if the boat ever sank quickly, we would be pulled down with the boat. The thought was quickly dismissed as that never happens on Georgian Bay.

Once away from the Midland Bay Sailing Club docks, we tacked back and forth in front of the starting line deciding upon strategy and future sail changes. The first leg of the race was a broad reach on port tack and the large white green and yellow spinnaker was chosen for its reaching ability. We recorded the time intervals as we made our many passes by the Committee boat and the start line while calculating both our position and the required time for Emigrant to hit the start line as the gun went off. Andy nonchalantly commented that the start does not mean a great deal in a long distance race. As the red flag went up, the gun fired, and Emigrant was first over the starting line.

We hoisted the spinnaker immediately and it exploded into a plump rigid cup, accelerating the boat forward. The winds were gusty and we fought the spinnaker sheet and guy, with the leading edge on the verge of collapse. Each gust drove the starboard rail into the water, driving Emigrant forward. I catapulted myself out over the port side to counteract the gusts and attempted to keep the rail out of the water. Looking to our stern the brilliant blue morning sky was illuminated with a kaleidoscope of colour from the many spinnakers of boat behind us. As I was admiring the sights, the boat lifted out of the water as if we were riding the crest of a wave, and our speed multiplied. Andy’s calm voice announced, “We’re on a plane.” He asked me to haul in on the guy line. I furiously looked for the proper line amid the maze of controls. Finding it, I gave her a tug. Andy calmly said, “Relax, think before you move and you’ll avoid mistakes”. Of course I realized he was right but this boat was so complicated compared to my Cygnus. What an exhilarating feeling as the noise of the wind and water was amplified by the sheer speed of the boat. Whatever speed we were going, it was faster than I ever sailed before.

Thundering out of Midland Bay, we rounded Midland Point and began to head up into the gap. Camp Simpresca was in clear view where I spent the last night with the crew of Destination Sainte Marie before arriving just a month before. I recalled very fond memories of rendezvousing with Joanne that evening, after paddling and portaging for 40 days. I was glad to be back. A crisp order to “douse the chute” brought me back to reality. Lynda and I quickly brought in the spinnaker and hardened up the head sail for the reach up the gap to Adam’s Point. The wind velocity was abnormally high. Emigrant drove forward, as Lynda and I hung out the port side. I found it rather comfortable, as the boat pounded through the waves, fighting both the building seas and the gusts. Getting back into the cockpit was a struggle and my long legs were definitely a disadvantage. I was totally impressed by Lynda’s ability to pop in and out.

The seas were running at about four feet and Andy attempted to let the air out of the main sail to prevent being overpowered. The sail flapped and cracked making a tremendous racket. The winds remained gusty and by this time I had been dunked and smashed by several large waves while hiking out over the side. Andy was right; the rain gear did not work too well. As I hiked out my back was horizontal to the water and the water, which had entered the rain suit puddled around the small of my back. I kept hoisting myself up into the cockpit when I had the chance to let the water drain down my legs.

By this time we had a substantial lead on the entire fleet. Despite the moderately heavy conditions we were doing well. I was glad I decided to go with Andy and Lynda rather than taking my boat. I would have turned around at Midland Point with this weather.

I watched the rigging on the boat strain, as I hiked out over the side. Lynda was positioned ahead of me and Andy behind. Lynda and I were pounded with waves on a regular basis and I remembered thinking to myself that Linda’s face reminded me of the face of one of the sailors on the cover of SAIL magazine who participated in the disastrous Fastnet Race of 1979. Her hood was up, her face full of intensity and water dripping everywhere. The main sail was flapping hard, giving the cracking sound of a helicopter rotor blade. I noticed the registration number of the boat was KC113. I recall hoping the last two digits were not significant. The boats behind us were also struggling. The light displacement Megas in particular seemed to be heeled 35 to 40 degrees but the fleet pressed on. Amidst the intensity, there were moments of calm as the sun was on my face, and I had all the confidence in the world in both the boat and crew. I recall looking behind me at the water and being able to see the shadow of our large keel cutting through the water as Emigrant heeled. Lynda continued to go into the cockpit to make adjustments to the sails as I hung out the side. At one point she entered the boat, made an adjustment and threw herself back out over the side to join me in the hiking position. Somehow her hackle cord and lifeline had come undone in the base of the boat. As she catapulted herself out over the side, she realized she was not connected to the boat and she desperately grabbed the handholds of the deck of the boat. Her upper body rocketed over the side and her feet went straight into the air. I grabbed her arm and back as Andy raced forward to haul her in. Somehow Andy had kept one hand on the tiller through the excitement and the boat rocked but quickly regained composure. After a flutter of anxiety we settled down and made sure all lines were secure. Again, Lynda impressed me. She shook off the scare, regained composure and continued to hike and make the necessary sail adjustments. I heard Andy comment to himself that he had let the mainsheet go but the boat did not “round up” into the wind to right itself. I suggested that the power of the wind in the jib probably kept the boat driving forward.

The wind was blowing due west and it looked as if it was blowing 25 to 30 knots by my recollection of the Beaufort scale. As we approached Adam’s Point we were hit by the full force of the westerly blow. We sighted a large trimaran which had set out for a long trip to Toronto that morning. She had turned around and was heading back to Midland. We thought she probably had mechanical problems.

Andy decided to take down the mainsail to reduce power and eliminate the tremendous cracking noise. He had been “ragging” the mainsail to let the air out, but it didn’t have any impact. I brailed the main sail around the boom and tightened the main sheet, to prevent the boom from banging around. The boat continued to drive forward and we continued to hike.

By this time I was wet and began to get chilly. The winds seemed to increase slightly in velocity, and the waves were building in the open water. I was hit on several occasions by the full force of waves while hiking out knocking me sideways. It felt as if someone hit me in the rib cage with a baseball bat. On one occasion, Lynda was going from the hiking position to the cockpit in order to make a sail adjustment when she was hit by a wave. It shot her into the boat and she smashed her head against the boom. Again she gained her composure and kept sailing without complaint. She is one tough lady.

By this time two other boats were catching us. Sidewinder, the other Soling in the race, had kept their mainsail up, along with their jib and was doing quite well. Steadfast, a 40-foot C&C yacht, was also driving on. The three boats crossed each other’s paths several times on the beat out to the Tomb. Andy felt this was the most difficult point of sail as we were heading right into the wind and if we could hold our lead and course, once we rounded the green can off the south end of the Tomb we would be all right. As we approached the Tomb I began to shiver. There were long stretches of silence in which I questioned the logic in what we were doing. I recalled my DSM training and attempted to lessen the amount of skin, which was exposed by rolling my turtleneck over my chin and hat down to my eyebrows. Just then Sidewinder sailed by and only one man was sailing her. We noticed the other two crew members were below in the cockpit attempting to stay warm. Andy said, “You’ve got to dress properly if you’re going to be out here in this.” They must have been freezing because I was cold and I had the rain suit and all my wool clothes. They were dressed in blue jeans.

Not long after, Sidewinder decided they had had enough, turned and began to run for home. I also noticed several other boats leaving the race, including two of the Megas. Lynda surveyed the water and thought only three boats remained in the race, a Mega, Steadfast and us. We held our course and headed for the green can. Lynda remarked, “Andy, this isn’t fun anymore,” and she was right, it wasn’t. We continued to pound our way, rounded the green buoy and headed north-west, on our new course towards Hope Island. Violent was the only way to describe this sail. As I strained over the side, I kept my eyes on the horizon and noticed this band of white separating the dark blue, white-capped seas from the light blue sky. Turning to Andy, I attempted to shout over the noise and pointed to the horizon in front of us. Andy shouted with fright, “Look at that!” We were looking at a thickening horizontal line of white mist located just north of Beckwith Island. With fear in his eyes, Andy shouted orders to come about and pulled the tiller towards him. Emigrant responded immediately and we began running for home. I remember being relieved that we were on our way home.

For a second or two it looked like fog, but in an instant it hit us with such intensity, it was almost beyond belief. Hail, rain, and unbelievably strong winds. I looked towards the bow of the boat and it was barely visible. The seas around us were white, as the tops of the waves were being blown off and we were charging forward in a sea of violent foam. The waves, it seemed, were running six to eight feet. Emigrant was running under the jib but the wind was so strong that the boat seemed to be on a plane. It made no sense but the speed was ferocious. Andy shouted, “My god, we could get swamped!” Oddly, I remained calm, probably out of ignorance. By now the air was filled with flying spray, and it felt as if we were inside this foam bubble with only the interior of the cockpit visible. It was surreal. The hail hurt as it pounded us, and the air was so strong we had to turn away to breathe. I looked into the cockpit to get my breath and I could see the mast bent forward so far that I could look up the interior of the mast at the step. I thought it may break at any moment.

Soon the wind’s strength drove the jib forward and its power drove the bow down to starboard side and we were taking in water over the starboard bow. We tried to hike to port but it was useless. Water rushed into the cockpit and we all feared the boat would pitch-pole. Andy tried to head the boat up in lee of Giant’s Tomb but she wouldn’t turn into the wind. We were sailing without a motor, so we had to keep the sail up in order to have some power and control, otherwise we would be even more at the mercy of the gale. Buckets and other gear began to float away as Emigrant listed badly to starboard. I located a red bucket and started to bail. Lynda hauled out the life jackets for her and I, as Andy always sailed with a jacket. In thinking about this situation, I can’t believe we didn’t have them on.

Bailing was useless, as the water rushed in faster than I could bail. I recall saying to myself, “Don’t waste your strength. You’re going to need it later.” I had forgotten about my leg hackles and after tripping over the hackle line noticed my predicament. I had a difficult time getting my feet out of the hackles and remembered thinking, what would I have done if it went over. After releasing my legs, Lynda reached over and undid my chest harness. We all hung onto the port gunnel waiting for the inevitable. The boat was now half submerged and it was definite that we were going down. Andy sat on the gunwhale attempting to steer the boat north. Lynda handed me a life vest but I struggled getting the vintage Elvstrom jacket on. The one clasp securing the front of the jacket was old but after a couple of minutes, I had it on. Andy was praying out loud. Amazingly, again DSM came back to me, and I reached into the cockpit for my extra gloves and anything I could find to put on. I began to put on the gloves and Andy asked what I was doing. I offered the gloves to him and told him to bundle up. I thought it might relieve his anxiety, which was now obvious.

We were slowly going down, but the wind velocity seemed to be diminishing. Visibility was improving but the entire world was grey and violent. The noise of the wind was steady, but the silence in the boat was daunting. Oddly, I felt a sense of calm. I waved my red bucket at two boats that were now barely in sight. I could distinguish the large stripe of a Mega with all sails down, stationary about two or three miles south of us towards the mainland. The other boat was in the same vicinity of the Mega but was sailing east under the jib at a tremendous speed. Andy commented that nobody was coming to help us. I waved my red bucket hoping someone would see us.

During the entire time Linda had been quietly working away. She sorted lines, cleaned the cockpit, as best she could, looked for car keys and held onto the gunwale. I remember watching the beautiful white, green and yellow spinnaker float away. This was Andy and Lynda’s favourite sail. Nothing was said, as we all watched in silence as it floated and sunk to the stern.

The Tomb was now barely visible and it seemed miles away to our windward side. The winds remained constantly intense and the seas seemed to be building. However, the rain and hail had stopped. I recall looking at the bow, which was now higher out of the water than normal, thinking, “This is tragic.” What a sorry state of affairs—the boat listing badly to starboard, half submerged and sinking to the stern, one or two miles east of Giant’s Tomb, four or five miles north of the mainland. and no help in sight. I looked over at the Mega and it was still stationary, however we continued to creep north, away from her. I believe Andy was in shock and he kept shouting that the others had abandoned us. I thought perhaps that the Mega had seen us, however I didn’t know if they could see that we were sinking. Our mast was at about a 45 degree angle now and the port side of the boat was out of the water. I thought the crew of the Mega may have thought we were still sailing and simply heeled over due to the wind. Lynda and I were in the cockpit hanging onto the port gunwale. I turned to Andy and asked him if he had any signal flares. He replied that he didn’t.

We had reached the point where one wonders if there is anything else that could be done, and not wanting to leave the safety of the boat, we hung on watching the angry seas batter us and feeling the violent wind tear at our faces, in silence. A wire shroud had snapped with the force of the wind and it was wildly cutting through the air. It was obvious the time had come and we knew we had to abandon the boat. Andy continued to pray. I broke in and said we must stay together when we go in. “Let’s lock arms at first and stay with the boat as long as possible. When and if it begins to go down, we must get away from the boat together.” Andy said, “Don’t leave me. I can’t swim”.

The boat continued to fill and the shroud and halyards were whining overhead. I motioned to Linda and climbed onto the freeboard. I helped Andy up and checked his jacket. I recall praying, “Please God, for Joanne, Kaitlin and Benjamin’s sake, don’t let anything happen to me.” The three of us went into the violent seas on the windward side of the Soling. We stayed with the boat for a while but another shroud broke away and started flapping around. Linda suggested we get away from the boat in fear of someone being injured by flying debris, as the entire rig looked as if it was going to come down. We pushed off, locked arms and Andy immediately panicked and pulled Lynda and I under. I pushed off violently as my mouth filled with water, and kicked myself to the surface coughing and gasping.

At this point something happened and I was hit by a wall of water and tumbled uncontrollably. Struggling to the surface again, panic-stricken and coughing water, I searched for my crewmates, but Lynda and Andy were nowhere to be seen. I was on my own. Good old DSM training kicked in and I began to kick my feet, turning myself to face the waves preventing any surprises from the waves. Keeping my arms tucked close to my body and my legs crossed to help prevent heat loss, I bobbed in the water with some degree of control. I pulled my hat down, my turtleneck up to lessen the exposed area but maintain my vision, and kicked off my shoes. With relief, I could hear Lynda screaming instructions at Andy—“Keep your mouth shut—look at me.” I was within earshot of them, about 20 to 30 yards away, but downwind. I attempted to shout back but my voice was lost in the wind. Surprisingly, and perhaps naively, I was calm and felt in complete control. The seas were running 6 to 10 feet and I was submerged every sixth or seventh wave. However I could see them coming and I simply rode each wave out. I wondered how long I could last, as every sixth or seventh wave was larger than the one before. I was relatively warm; in fact the water was warmer than the air. My muscles felt fine and I was sure I could last a couple of hours if I maintained my composure. Soon the sun broke through and the clouds cleared. I remember how ironic this day was, starting out as a beautiful day with hope of adventure and here I was hoping for my life. I could hear Lynda talking to Andy, telling him to relax. Every once in a while I could catch a glimpse of them. They were now about 30 or 40 yards upwind, to the right of me.

I continued floating, kicking, breathing, and watching for the waves and preparing for the inevitable swamping. I tried not to think of Jo and the kids as each time I did, anxiety would build, my feet would sink, and I was in trouble. So I concentrated on breathing, watching the waves and thinking of my next move. I was confident now and in control, continually reminding myself to stay vigilant and try to ride out the day. Lying on my back, with the sun warming my face, I recall trying to calculate how fast I was being pushed eastward, and when I may end up on the west shore of the islands. My thoughts were interrupted by the sound of a rather distressed outboard motor struggling through the heavy seas. She was about a 26-foot white hulled sailboat, with the number 10 on her mainsail. I couldn’t understand why she still had her sail up but I wasn’t arguing. They headed for Andy and Linda first, but had some difficulty picking them up. In fact after their third unsuccessful pass they sailed away and I thought they were leaving. However, they came back and made five or six passes. In a few minutes I saw Lynda being towed by life ring to the other rescue sailboat. I feared for Andy’s life as I didn’t see them pick him up.

I waited for my turn. Astonishingly, the boat sailed away. I couldn’t believe my eyes and I gave two loud screams before I heard another motor behind me. Another boat appeared 20 yards to my right. It was the blue Mega. By this time, I had lost some of my confidence and discipline and I tried to turn and wave to the oncoming vessel. The Mega approached me from the leeward side, I assume in fear of running me over. A crew member standing amidships attempted to throw me a life ring but the wind was too strong and the moment it left his hand, the wind threw it away. In the next run they attempted to throw a line to me from the bow pulpit, but again the wind rejected the attempt.

By this time I was becoming more relaxed as help had come and rescue was inevitable. I thought it was all over. The Mega made several more attempts and during the process I was surprised by three or four good sized waves and I took the same number of mouthfuls of water. I immediately panicked and started to kick and flap my arms. I was going down, flapping my arms and legs, coughing underwater and taking in water. I don’t know why, but for some wonderful reason I stopped panicking, crossed my legs and grabbed the chest of my lifejacket. The jacket did its job and I broke through the surface of the water gasping, choking and throwing up. Shaken, with lungs burning, I began to talk to myself out loud: “Relax, just take it easy, you’ll be all right, turn into the waves, kick your feet—watch the wave—prepare—think”.

The Mega returned soon after and circled me, dragging a life ring on about 100 yards of line. With a lesson learned, I maintained my position, watching the waves. As the Mega circled me the line kept getting closer and closer, but I refused to be lured into reaching and risking another swamping. I watched and waited for the line to hit my nose, then grabbed and hung on. I saw Harvey Payne hauling me in from the stern. Even at this time I had seemed to have regained this sense of calm and lack of emotion—perhaps it was my way of dealing with it.

I reached the boat and was helped into the boat by Harvey, his son Tom and a well-designed stern lip, which allows one to get a foothold on the transom. Upon arrival on deck I smiled, introduced myself as Bill Byrick and promptly shook everyone’s hand. In retrospect, I can’t believe how I reacted. It was as if I was Dr. Livingstone and I had just crashed through the jungle and fell upon a British search party. What a goof! I asked if Andy had been picked up. The answer was affirmative but both Lynda and Andy’s condition was unknown. Harvey invited me down into the cabin to change into dry clothing. His wife Marg was below feeling the effect of the high seas. She welcomed me aboard and promptly said, “Excuse me but I’ve been throwing up for quite some time.” By this time, it was the furthest thing from my mind. I quickly rid myself of my rain gear, sweater, turtleneck and T-shirt. Harvey kept reappearing through the hatch asking me if I would like something to eat or drink. Marg Payne had given me a cup of hot water and that satisfied my needs for the moment. I noticed I was shivering quite heavily. I quickly slipped on a dry wool sweater and cotton jacket. My sweat pants remained wet but I did not have an alternative. The yacht was being tossed around like a cork and inside the cabin I began to feel the effects that inflicted Marg. I decided I had better get out into the cockpit before the water I had swallowed would project back into Georgian Bay! Once outside Harvey noticed my wet pants. He immediately provided two sleeping bags, pants from his foul weather gear and a hood that Harvey quickly tied around my neck.

I cannot say enough about the Payne’s hospitality. The boat that rescued Lynda and Andy sailed past to see if I was safe and I noticed my crewmates sitting safely in the cockpit. A strange feeling came over me as I held my cup of water up to them, as if it was a toast to our accomplishment. They returned my toast to life.

Under a reefed main the Mega sped homeward before a 20-30 knot wind and high seas. For the first time I had the opportunity to discuss the incredible happenings of the last two hours. Basil, an elderly crew member, was quite calm and analytical about the events. He was quite pleasant and enjoyed discussing the Destination Sainte-Marie experience. I noticed long studying stares at my face, by the three Paynes obviously looking for signs of hypothermia, shock etc. At one point Marg commented, “I don’t think his colour is right.” Tom, her son replied “Mother, I think yours is worse.” The warm layers of wrapping and the welcome, warm feeling among the crew made it quite comfortable. As we surfed southward down the gap I noticed the OPP cruiser General Williams and the large yellow search-and-rescue helicopter scanning the water for survivors and wreckage. I wondered how many other boats went down.

Harvey offered to take me directly to his home for a hot bath, since he lives on the waters of Midland Bay. I decided to return to the Sailing Club to see if Andy and Lynda were OK, and return home to see Joanne and the kids. I had a craving to see them. I readied myself and gathered my damp clothes, life jackets and hiking harness for departure.

Upon arrival at the dock we were greeted by a crowd of very concerned sailors, asking about the wellbeing of Andy, Lynda and myself. They requested information about Sidewinder, the other Soling. We had none. A woman, who seemed to know what was going on, reported that there was no sign of the other Soling. For the first time an awful gut-twisting knot developed in my stomach. I recall thinking optimistically that they may have made it to shelter.

I thanked the Paynes once again for saving my life, and ran over to Andy’s van to retrieve my car keys. It was locked. Dave Maitland asked me about the sinking and suggested I go warm myself by the fire in the clubhouse. While jogging over to the club, Chris Tully shook my hand and said in a nervously quiet voice, “Christ, it’s good to see you.”

Upon entering the clubhouse I borrowed a quarter and phoned Joanne. The line was busy. I knew knew Jo had a tendency to lift the receiver off the hook in the afternoons when the kids were sleeping. I felt she probably knew nothing of the events of the Hope Island Race. Seeking the warmth of the fire, I stood attempting to put my thoughts together. Four or five people had the same idea and my appearance brought forth a barrage of questions. After several minutes I had to get out of there and decided to borrow a car and go home. I ran outside and saw Jim McConachie down by the wharf. He informed me Andy and Lynda had been taken to Wye Heritage Marina and he heard three people from an unknown boat had been taken to the hospital. We all prayed it was the crew from Sidewinder. Jim loaned me his car and I drove home to my family.

As suspected, when I arrived, Joanne was asleep on the couch and the kids were fast asleep upstairs. All were totally unaware of my adventure. Jo wondered why I was home so early, dressed in strange clothes. After a quick explanation I laid down beside her under the woolen throw.

After a soothing shower I returned to the sailing club to see Andy and Linda and retrieve my car. Jo and I were going to return to the club for dinner but I wanted to see how everyone was. By this time it was 4 p.m. Upon arrival back at the club I noticed John McCallum, the Commodore and a friend, in the hallway of the club. He immediately came over to shake my hand and welcome me back. John informed me of the death of one crew member on Sidewinder. Chills ran up my spine, my muscles tensed and I felt nauseous. I had never really thought of anyone dying. My first reaction was what a waste! I thought of his family and how they must feel. I left the club and drove home in my car. By this time I was quite shaken. I told Joanne of the tragedy upon arrival. Our house was filled with emotion as we held each other. There was unbearable silence, yet further discussion was even more unbearable.

Someone had recommended that I should go to the hospital. Apparently everyone else was there! Jo and I packed the kids into the car and drove to the hospital. I registered at emergency at HDH and soon a nurse took me into the examining room and took my temperature. While sitting on the stretcher, I noticed my fingers trembling. In a few minutes the thermometer was checked and I was a normal 37C. Shortly after, a familiar voice was heard behind the cloth curtain. Dave Parsons, the fellow I had asked to crew with me on my boat, appeared. Unfortunately, he did participate in the Hope Island Race after all! Dave wanted to know what happened and I’m sure he wanted to see if I was coherent. From Dave, I heard Sidewinder and a large sailboat had sunk; Dave Desroches, skipper of Sidewinder, was hospitalized in shock; two men were dead and the crew of an airplane that had gone down on Beausoleil were hospitalized. After asking several questions about hypothermia, Jo, Kaitlin, Benjamin and I returned to the sailing club.

The clubhouse was full of people. I located Andy, shook his hand and asked him how he was doing. He was obviously upset but OK. To my surprise he apologized for what happened. That certainly was not necessary and I told him so. After talking very briefly I located Lynda, and made my way to her and laid on a big kiss. “Boy am I glad you were with us today,” she announced. I brushed the compliment off because I didn’t really know why she would say that— perhaps because she was alive! I simply said, “Lynda, you saved Andy’s life.” She talked a little about how cool we were and proceeded to say it wasn’t that bad out there. That was a bit too much for me so I retreated to the security of Joanne. Lynda is undoubtedly one of the gutsiest ladies I have ever known. Joanne is another, but she will not admit it after the pressures of Destination Sainte-Marie. I seem to test her courage regularly.

The evening proceeded with a dinner and much discussion. Many people offered their relief of my safe return and wanted to hear the stories. I noticed many people looking at Kait and Ben with a kind of pity, fear, disgust and relief. I’m sure people were asking the same question I was asking—“Why risk it?” Those left behind are always the real losers, and my heart went out to the families of those who died. I was really uncomfortable in the room. On one hand people were relieved to see us back safely and they wanted to hear about the events, and I felt I should share my experience so everyone would know the terrifying facts. But on the other hand my gut turned with anger as we sat socializing while two men were dead and families grieving. I just wanted to get out.

John McCallum stood up and said a few much-needed words of praise for the rescuers, relief for the survivors, and grief for the dead. He also pleaded for more safety on the water. Jo and I thanked the Paynes again for saving my life and left.

That evening Dave and Eleanor Hudson dropped in to see if I was OK. I poured stiff drinks and went through the entire day’s events. I was very glad to climb into my safe, dry bed that evening with Joanne.

The next day I woke at 8 am, ate breakfast and proceeded to chop wood from 8:30 to 4:00 pm with frequent breaks to respond to numerous calls about my wellbeing. Throughout the day I had flashbacks about the race, the sinking and the surviving. Each time shivers would crawl up my back. I kept contemplating the feelings of loneliness, dependence, vulnerability, trust, fear, calm, panic, death, life, sympathy, disgust, and love which I felt on August 28, 1982. That evening I sat down and wrote this memoir.

Many lessons were learned on August 28, 1982, and the events will live with me and many others for years to come.

—Bill Byrick

About the Author

Although never a club member, Bill Byrick was well known to MBSC, crewing for a variety of members in club events and entering them as well with his Cygnus and later his Shark with his wife Joanne out of French’s Marina, where Bay Port Marina is now found. Bill was director of Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons from 1977 to 1990, director of Discovery Harbour from 1990 to 1996, director of the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough from 1996 to 2002, and director of Athletics at Trent University from 2002 to 2013, after which he and Joanne moved back to Midland.

Although never a club member, Bill Byrick was well known to MBSC, crewing for a variety of members in club events and entering them as well with his Cygnus and later his Shark with his wife Joanne out of French’s Marina, where Bay Port Marina is now found. Bill was director of Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons from 1977 to 1990, director of Discovery Harbour from 1990 to 1996, director of the Canadian Canoe Museum in Peterborough from 1996 to 2002, and director of Athletics at Trent University from 2002 to 2013, after which he and Joanne moved back to Midland.